It sounds like something from a sci-fi blockbuster: giant viruses are living in the Arctic ice. But the earth is not doomed – these supersized infectious agents could actually help slow the melting of the ice, helping to alleviate global warming.

According to findings published in May in the journal Microbiome, researchers at Denmark’s Aarhus University discovered the giant viruses in Greenland. They suspect they may slow the growth of black snow algae – which contributes to ice-melt.

What exactly are giant viruses?

Normal viruses are around 1,000 times smaller than bacteria, but giant viruses – first discovered in the ocean in 1981 – are bigger in both size and genome. They can grow to 2.5 micrometres, where most bacteria are around two micrometres.

Giant viruses have around 2.5 million letters in their genome (the complete set of genetic material in an organism, stored in its DNA) making them vastly more complex than regular viruses. For instance, bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) only have from 100,000 to 200,000.

They’ve been found in the oceans, soil and even humans, but this is the first time giant viruses have been discovered in the snow and ice dominated by pigmented microalgae.

What’s the problem with algae on the Arctic ice?

The Arctic teems with life, from walruses and polar bears to birds, fish, plankton – and algae. Each spring, warmed by the sun, this algae starts to bloom, blackening the ice on which it grows. This reduces the ice’s ability to reflect the sun and accelerates ice-melt.

Arctic ice is diminishing fast and the polar region could be completely free from ice by 2040, with its loss affecting global temperatures, creating weather extremes, endangering coastal communities, risking food stability, contributing to wildlife decline and risking methane release from the permafrost.

Why is the discovery of giant viruses in the Arctic important?

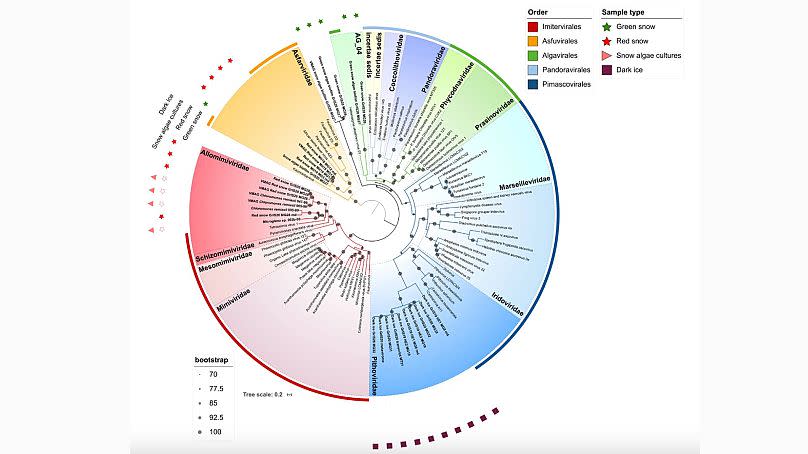

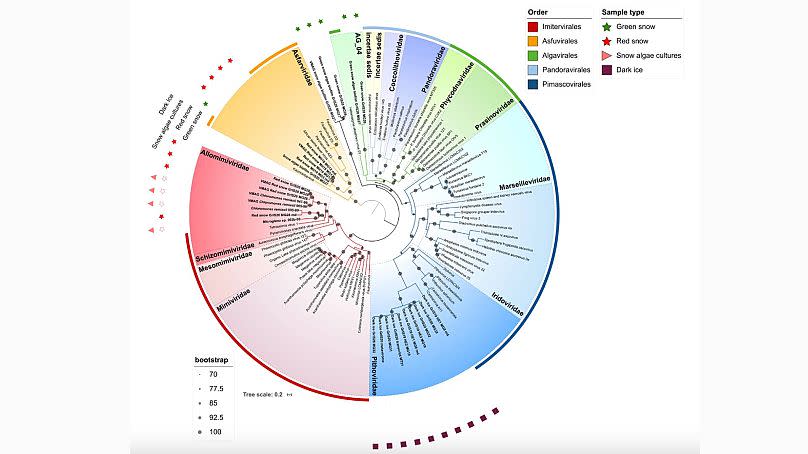

The Aarhus University research team, led by Laura Perini from the Department of Environmental Science, sifted through the Arctic’s dark ice, red and green snow (all characterised by high levels of algae), ice core and cryoconite (holes caused by sediment melting into the glacier) to discover a thriving ecosystem.

Alongside the algae, the scientists identified bacteria, filamentous fungi, yeasts, protists (organisms that aren’t animals, land plants or fungi) that feed off the algae, and the giant viruses – which they suspect infect the algae.

“We don’t know a lot about the viruses, but I think they could be useful as a way of alleviating ice melting caused by algal blooms,” Perini explains. “Which hosts the giant viruses infect, we can’t link exactly. Some of them may be infecting protists while others attack the snow algae. We simply can’t be sure yet.”

Another research paper from the same team will be released later this year, featuring giant viruses infecting “cultivated microalgae thriving on the surface ice of the Greenland ice sheet,” says Perini. “We specifically looked for those giant viruses because we are investigating the possible top-down controls of the dark pigmented algae blooming on surface ice of the Greenland ice sheet. Next? I am focussing on parasitic fungi, another possible controller of these microalgae.”